(Yes, I'm well aware of the huge disturbance in the force that happened just over a week ago. I'm sure I'll get into that that at some point, possibly when/if the dust settles. In the meantime, I did get most of my thoughts out in this tweetstorm.)

No, seriously. 17 years of divisional play and I still can't get it right.

The ACC has done away with divisions, and in doing so will likely be the first Power 5 conference to make the move to divisionless football for a league of 12+ members. Rather than division champions meeting in Charlotte in early December, the two best conference records - tiebreakers withstanding - will play for the championship. The move meets two goals: First, having the top two teams meet gives the conference the best chance to put a team into the College Football Playoff: Whichever team wins will pick up another quality win, and there's no chance of, say, a 7-5 division champion pulling an upset and scuttling the conference's chances. It also ensures that conference teams will meet as often as possible: Each team will play its three permanent opponents annually, and meet the remaining ten teams twice every four years, ensuring a home-and-away experience on each campus for any four year players. In doing so, they combat one of the less savory aspects of large conferences: conferencemates meeting so seldom that any shared affiliation is merely a formality. Famously, SEC conferencemates Georgia and Texas A&M have met just once in the decade that the two have shared a conference.

The SEC's expansion, in fact, may very well have set the wheels in motion for this style of scheduling. With the expansion to two seven-team division plus a permanent crossover rival, SEC teams could only cycle through the rest of the opposite division opponents once every six years. At that point, someone more clever than I mapped out the 3-5-5 scheduling model the ACC now employs; quite a few folks took a shot at mapping out permanent rivals. I was one of them. Still, the SEC's longevity and relative stability as a conference led to more natural pairings of permanent opponents, such that mot models looked pretty similar in what matchups they preserved.

In contrast, the schools of the ACC vary greatly in terms of longevity with one another. Charter members like UNC and UVA have faced one another in the South's Oldest Rivalry since 1892, while Louisville, the league's newest member, shared the Big East with a few current members, but as both a temporal and geographic outlier has little history to speak of. Some programs bring history from previous leagues with them; Some rivalries are more recent constructions.

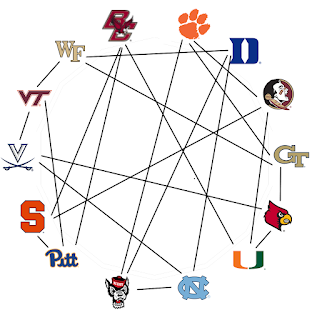

To begin with, the schedule made all of its lobs, preserving FSU-Miami, Virginia-Virginia Tech, and UNC-Duke and UNC-NC State. Clemson-NC State maintain the Textile Bowl as the Carolinas' land grant PWIs; old Big East tilts like Pitt-Syracuse and Boston College-Miami remain as well (curiously enough, Miami-Louisville, both former Big East members but never simultaneously, are also paired). The slate features a few closed triangles: The northern triumvirate of Syracuse-Boston College-Pitt, and the Research Triangle of UNC-NC State-Duke. Like geographically, Wake Forest breaks with its Tobacco Road brethren, matching only with their Methodist counterparts at Duke.

Still, even the misses won't be strangers, as league opponents not protected will still play 50% of the time. The ACC is slated to begin this schedule in 2023; the SEC and Big Ten are currently exploring how future schedules will look for them, though recent and future realignment will certainly play a role.

Comments